Why do we sing? What is it about song that is so powerful? How does singing shape how we see ourselves and how we relate to one another? For MUSLIVE, one answer to such fundamental questions is historical; singing, after all, is not only a practice which is shared across languages and cultures, but also spans the many centuries and millennia of human history.

Medieval French song as a case study

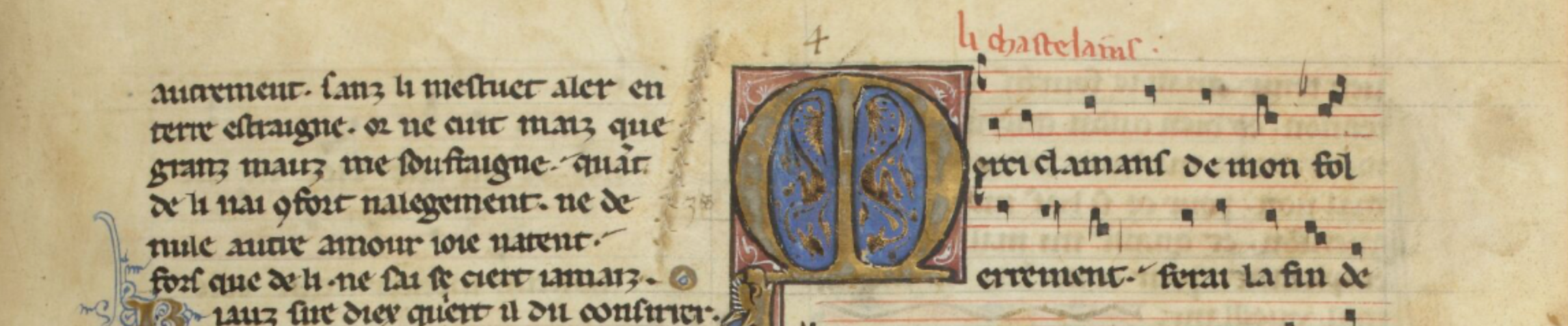

MUSLIVE’s case study is the tradition of medieval French song, known as trouvère song. Along with Occitan troubadour song, trouvère song holds a special place in the history of music and literature. Although certainly not the first vernacular (non-Latin) poetic tradition in western Europe, it was among the first to be systematically written down: from the early decades of the thirteenth century through to the fourteenth century, trouvère poetry was inscribed in dedicated songbooks known as chansonniers. Crucially, unlike the troubadour corpus, the vast majority of trouvère poems were notated with music.

Many of these songs are, moreover, connected to specific people through acts of self-naming, references to other trouvères in songs, and through attributions in chansonniers; these people are often identifiable figures who also appear elsewhere in the historical record. So, while we know that people sang love songs before the medieval period, the trouvère tradition offers, for perhaps the first time, insights into the songs people sang and the lives of those associated with song production.

Image source: gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France MS français 844 f. 87r

A multi-disciplinary approach

The project research brings together approaches from musicology, literary studies and history to generate fresh perspectives on trouvère song and the research questions above. We approach song-making as a living practice through a detailed exploration of the songs themselves, their transmission patterns, poetic and melodic craft, the worlds created within their texts, and the connections between songs.

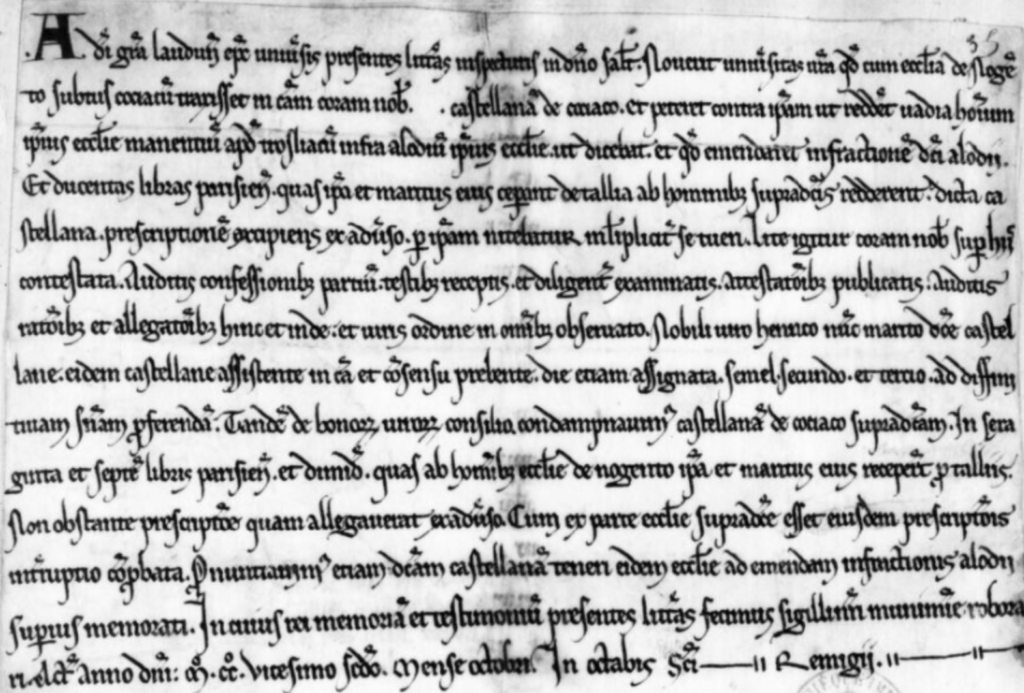

We bring this together with evidence from Latin charters – documents pertaining to land and rights to land – to revisit the people associated with the songs, building a sense of their lived experience, their networks, and the world around them. We ask who they were and how these documents can enrich our understanding of their musical and poetic practice. These two strands – people and songs – are brought together to answer the question: what cultural work did medieval song do?

In the first phase of work, our focus is on people and songs linked to the first two generations of the trouvère tradition, with a focus on well-known makers, such as the aristocratic Châtelain de Coucy, as well as those who have been less well studied to date, like Jehan Bretel. Using database tools, we will build up a picture of these individuals and the social circles in which they moved, expressed in pious donations, canny exchanges and disputes over property, as well as in their own works. The research will focus on the themes of identity, itinerary and sonic networks.

Image source: gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France MS Picardie 291 f. 92r

LISTENING TO THE WHOLE ENSEMBLE: ARABIC AND HEBREW POETRY

Central to MUSLIVE’s approach to these themes is the recognition that we cannot fully understand what medieval French song is and does without understanding other textual and poetic traditions with which it shared sonic spaces and cultural worlds. This goes beyond looking at French trouvère song alongside documentary records. The travels of French song-makers beyond northern France and around the Mediterranean also compel us to ask: what happens when we expand the linguistic, cultural, material, and literary context in which we situate French song? Such a question can only be answered through a deep and rigorous engagement with multiple poetic traditions that were circulating in the Mediterranean at the same time.

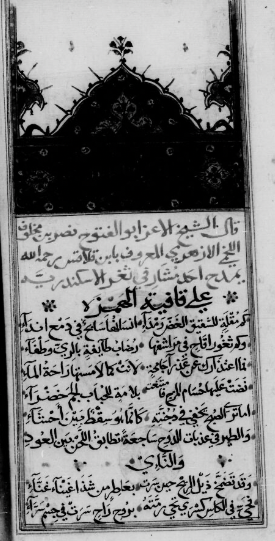

We recognise, then, the importance of attending just as closely to the poetic and musical production of writers and performers living in Arabophone Islamicate lands during the project period. We place a particular emphasis on the under-studied Ayyubid dynasty (1171-1260) founded by Ṣalāḥ al-Dīn ibn Ayyūb (Saladin), which at its height extended from eastern Yemen and Iraq to north-eastern Libya. In the process, we listen to and amplify voices that spoke, recited, or sang in Arabic and/or Hebrew; those belonging to members of Muslim, Jewish, Christian, and other religious communities; and those that were recorded in the Arabic language and script, the Hebrew language and script, and/or the Arabic language and Hebrew script (Judeo-Arabic).

The Arabic-Hebrew aspect of the project has several primary aims. It will survey poems and songs from within the project’s historical and geographical scope in a wider and more systematic way than has been done to date in English-language research, with a special focus on identifying the literary and performance networks that connected poets across space, those from Aleppo and Tunis to those from Alexandria and Aden. It will further focus in on what emotional, intellectual, and social force poetry and song had — and what individual poems and songs did — in Ayyubid Cairo, Damascus, and beyond. The research on Arabic-Hebrew poetry will be considered alongside the research on French trouvère song and its makers in specific ways, with a view to allowing resonances between the traditions, both sonic and cultural, to be heard.

Image source: gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France MS arabe 3333 f. 2

Listening for resonances

As our research develops, the project team will bring evidence together to generate case studies of places and times across Europe and the Mediterranean where human networks – and thus also potentially songs – moved and intersected. These “soundings” will provide concrete examples of the cultural work that poetry and songs did in different communities sharing a specific place at a particular point in time. They will also provide evidence of how song/poetic practice might link to the wider cultural and political forces at work in these worlds.

Our emphasis on soundings is also very literal: performance is an important part of MUSLIVE’s research methodology, as listening for resonances within and across song/poetic traditions requires these works to be spoken, sung, and heard. In addition to songs and poetic recitals, we attune to the performative dimensions of legal records, understanding them as part of the sonic environment that shared space with song practices.

In other words, then, MUSLIVE repositions French song as a transnational, cross-Mediterranean activity resonating within a larger ensemble of voices from across ethnic and religious lines. We listen for various kinds of potential resonances in the works and worlds of different song, poetic, and documentary traditions, from the possibility of overheard performance Outremer, to the parallel realms of consolation sought somewhere beyond everyday speech by a diverse group of song-/poem-makers traveling on a turbulent sea.

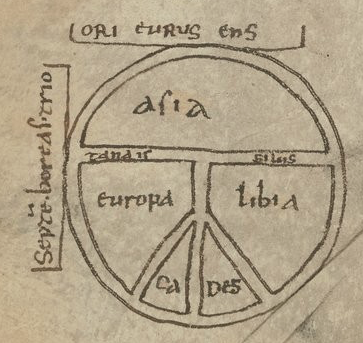

Image source: gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France MS Latin 12999 f. 7v